Back in May of 2006, there was a significant change to the tax laws involving IRAs. Starting in the year 2010, all taxpayers can convert their Traditional IRAs to a Roth IRA. That's an opportunity that not everyone had in the past.

In this article, we're going to talk about the Roth IRA conversion rule that went into effect in 2010. We'll also run through some of the strategies that individuals can use to take advantage of this change, starting today.

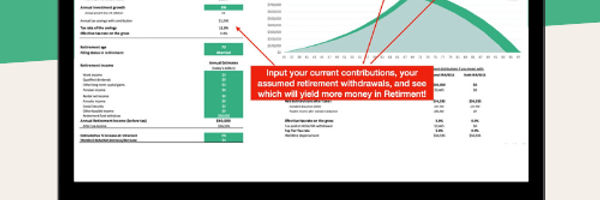

Roth IRA or 401k? This template will answer your questions.

With this template, you will get:

All DFY, simply add your details

Charts for comparison and clear answer

Easily update for any year (2023, 2024, 2025, etc…)

Roth IRA Conversion Rules

Additional Resources |

Under the current tax law for Roth IRA conversions, which was written in 1997, individuals were permitted to convert a Traditional IRA to a Roth IRA. There were only two stipulations that taxpayers had to worry about: paying taxes on the converted money and an income limit which determined eligibility to convert.

Converting an IRA

With a Traditional IRA, money can be placed into the account on a pre-tax (tax deductible) and after-tax basis. That investment is allowed to grow on a tax-deferred basis until withdrawn in retirement.

If an individual wanted to convert a Traditional IRA, they had to pay federal income taxes on any pre-tax contributions, as well as any growth in the investment's value. After all, once converted to a Roth, all of the investment could now be withdrawn on a tax-free basis in retirement.

Income Limits on Conversions

Unfortunately, that same 1997 tax law contained a provision limiting who could make a conversion. Upper income taxpayers, those with adjusted gross incomes of more than $100,000, whether single or married were not eligible to make such a conversion.

In addition, anyone earning $122,000 or more ($179,000 for married joint filers in 2011) weren't eligible to contribute to a Roth IRA. These two tax laws effectively precluded upper income taxpayers from enjoying the benefits of a Roth IRA. They couldn't convert their Traditional IRA to a Roth, and they couldn't fund one either.

IRA Conversions in 2010

But back in May of 2006, President Bush signed a $70 billion tax cut provision that changed the eligibility rules for Roth IRA conversions. Starting in 2010, taxpayers with modified adjusted gross incomes of more than $100,000 will be allowed to convert a Traditional IRA to a Roth. This change applies to all years beyond 2010, and the income taxes due on the conversion can be spread over two years. So the 2010 conversion amount may be included as taxable income in 2011 and 2012, helping to spread out the tax bite. Conversions in subsequent years are included in income during the tax year in which the conversion is completed.

Removing the conversion cap however doesn't mean anyone can fund a Roth IRA, but it does mean that anyone can convert an existing IRA.

Taking Advantage of the 2010 Rule

Fortunately, there is a way for all taxpayers, regardless of income, to take advantage of this change in the tax code:

Start Funding a Traditional IRA

Even if a taxpayer doesn't qualify to make Roth IRA contributions or Traditional IRA contributions on a before-tax basis, they can still make after-tax contributions to a Traditional IRA. By investing in a non-deductible IRA in the tax years 2006 through 2010, a conversion can take place in 2010.

Most investors shy away from making non-deductible contributions to an IRA because they are not tax deductible, the investment growth is taxable, and because they are subject to minimum distribution rules, they offer only a minimal tax shelter. But by converting these non-deductible IRAs to a Roth, many of those disadvantages disappear.

Roth IRA Conversion Examples

There is one important rule to keep in mind when converting: federal income taxes are due on any portion of the conversion that wasn't already taxed.

Example 1

Let's say John started to fund Traditional IRAs in 2006, and by 2010 he had $20,000 in his account. Furthermore, let's say this account consisted of four years of $4,000 non-deductible contributions. That's a total of $16,000 in non-deductible contributions plus $4,000 in account growth.

In this example, John would need to pay income taxes on the $4,000 in fund growth when he converts to a Roth IRA. But the good news is he'll never have to pay income taxes on this account again.

Example 2

In this second example, let's assume John funded that same Traditional IRA with before-tax dollars, meaning he was able to take a deduction on his tax return for the money placed in the account.

In this example, John didn't pay income taxes on any of the money in the account. When he converts it to a Roth IRA, taxes are owed on the entire account balance. In this case he'd have to pay income taxes on all $20,000 in the fund.

Example 3

If John has a Traditional IRA (with tax-deductible contributions) and he starts to fund a non-deductible IRA, then he needs to be aware that tax rules state that any conversion is done on a pro-rata basis. Let's say he had $100,000 in a deductible IRA and he had $25,000 in a non-deductible IRA.

If he wanted to convert $25,000 to a Roth, then he'd owe taxes on $20,000 because the pro-rata share of his non-deductible contributions is only $5,000.

Deciding to Fund a Roth IRA

While it might be very exciting for some individuals to learn they can use this 2010 law to convert an IRA, it's important to mention that a Roth is not for everyone. Before converting, it's important to understand the differences between a Roth IRA and a Traditional IRA. It's also a good idea to run through some what-if scenarios using a Roth versus Traditional IRA calculator.

It's always best to make an informed decision. Individuals with a question about what's right in their particular situation should consult with a tax professional before making any long-term changes.

About the Author - 2010 Roth IRA Conversions

.jpg)

.jpg)