Collateralized debt obligations take an asset and slice it into an investment that offers various levels of risk and reward. These asset-backed securities consist of bank loans as well as fixed income issues such as bonds and similar debt instruments. In this article, we're going to be discussing the topic of collateralized debt obligations, or CDOs. As part of that discussion we'll talk briefly about the history of these investments. Next, we'll talk about how CDOs are structured, including an example that demonstrates how the tranches might be sold to investors. Then we'll finish up with the pros and cons of these investments, including some of the lessons learned in 2007.

CDO as Investments

Back in 1987, bankers at Drexel Burnham Lambert, Inc. issued the first CDO. Also referred to as synthetic investments or asset-backed synthetic securities, the size of the CDO market would grow slowly until 2001 when David X. Li, a Chinese quantitative analyst, developed Gaussian copula models capable of rapidly pricing CDOs. In 2006, the global market for these investments would peak at $520 billion. The rapid growth of this market is attributed to the relatively high returns these securities offered investors. Typically, a CDO would provide returns that were 2 to 3% higher than bonds carrying the same credit rating. The way these securities were structured played a big role not only in their popularity, but also their downfall. The term collateralized debt obligation is used interchangeably with more descriptive subsets including:

CDO Type | Asset Used as Collateral |

Collateralized Bond Obligations (CBO) | Corporate Bonds |

Collateralized Insurance Obligations (CIO) | Insurance Contracts |

Collateralized Loan Obligations (CLO) | Bank Loans |

Commercial Real Estate CDO (CRE CDO): | Commercial Real Estate |

Collateralized Synthetic Obligations (CSO) | Credit Derivatives |

Structured Finance CDO (SFCDO) | Asset Backed Securities |

Structure of CDOs

At the core of this structure is a collateral portfolio. These are the debt instruments, which can be bank loans, fixed income securities such as bonds, or other forms of debt. As borrowers make payment, money flows into the CDO structure.

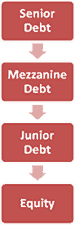

The CDO is then sliced into what are called tranches. Each tranche carries a different combination of risk and reward. For example, the selection of tranches might include:

Senior Debt: takes priority over all other tranches. This investment might be marketed at AAA quality, and holders of the tranche would be paid before all other investors.

Mezzanine Debt: next in line for payment. It's subordinate only to the senior debt and might be marketed as AA quality. Holders of this tranche will be paid before holders of junior debt.

Junior Debt: paid after both the senior and mezzanine debt and might be marketed as BBB quality. Holders of this tranche bear the greatest risk of non-payment, but they also receive the highest interest rate on the debt held.

Equity: there can also be an equity tranche in the CDO, and dividends can be paid to holders of the equity tranche once all of the debt holders have been paid.

To summarize the structure of a CDO, we have:

Collateral Portfolio: this can consist of a wide variety of debt, and as repayment of these loans are made by borrowers, money flows into the investment.

Tranches: the CDO is sliced into both debt and sometimes equity tranches. The tranches are sold following the principles of risk and reward. Senior debt carries the lowest interest rate, but also a lower risk of non-payment. The equity or junior debt tranches offer investors greater rewards, but also carry a greater risk of non-payment.

Fees: management and administrative fees can range from 0.5 to 1.5% annually.

The example below illustrates how the above structure works in practice.

Example Offering

In this example, there is a $100 collateral portfolio that is composed of debt at 6%. To pay for this collateral, the CDO is divided into four tranches:

$75.00 of Class A securities, with a credit rating of AAA, senior debt paying 5.0%

$15.00 of Class B securities, with a credit rating of A, mezzanine debt paying 6.0%

$5.00 of Class C securities, with a credit rating of BBB, junior debt paying 9.0%

$5.00 in Equity securities

In this example, the $75.00 of Class A would pay out $3.75 ($75.00 x 5.0%) in interest each year, Class B pays out $0.90 ($15.00 x 6.0%), and Class C pays out $0.45 ($5.00 x 9.0%). Of the remaining $0.90 ($6.00 - $3.75 - $0.90 - $0.45), $0.20 is used to pay for fees, leaving the Equity holders with a return of 14.0% ($0.70 / $5.00).

Pros and Cons

As is the case with most investments, there is always a balance of risk and rewards. The advantages and disadvantages of these investments are summarized below:

Pros

Junk quality debt can be bundled with investment quality debt, oftentimes rewarded with investment grade credit ratings.

Returns on CDOs are often 2 to 3% higher than corporate bonds carrying the same rating.

The investor has the flexibility to choose from several combinations of risk and reward.

Cons

Investors in lower tiered tranches are only paid if there is sufficient money to pay investors in higher tiered tranches.

If default results within the collateral portfolio, there is a risk of non-payment of interest owed as well as the remaining principal.

Market fears can result in a near standstill in trading, thereby creating a liquidity problem for the investor.

This risk of default is exactly what happened in the collateralized mortgage obligations market. The CMOs created back in the 2004 to 2006 timeframe were loaded with sub-prime mortgages. As long as homes increased in value, borrowers could continue to make payment on their mortgages, oftentimes using additional debt such as home equity loans. When the housing bubble burst, these sub-prime borrowers could no longer afford their monthly mortgage payments. Defaults on loans quickly followed, rendering CMOs nearly worthless. The fallout from these defaults was felt around the globe, and the $520 billion CDO marketplace would shrink to $4.3 billion by 2009.